This post was written by Courtney Leach, social media manager, Parkview Health.

I sat in a beige chair with worn wooden arms, cool and slick beneath my elbows. The long second hand stumbled around the clock above the front desk. It was 7:48 a.m. One of those cable shows where they do makeovers on rusty cars was on the television, just barely audible among the sparse gathering of loved ones in the surgical admissions waiting area at Parkview Hospital Randallia. The receptionist motioned me back and escorted me to my subject for the day, Geoffrey Cly, MD, PPG – OB/GYN.

We introduced ourselves, happy to put faces to our ongoing email chain. He was entering information into the computer and turned to me between typing.

“Already a crazy morning,” he said.

“Oh?”

“Yeah, my daughter forgot her lunch so I had to turn around and get it to her. So, you know, that’s a great way to start the day.”

Dr. Cly, a man who has brought hundreds of little ones into the world, has six children of his own, ranging in age from 20-year-old twins to a 3-month-old daughter. The healthy mix of boys and girls make up the lead characters in many of the stories he shares with staff and patients. During my day in his company, I would come to count the physician as many things, proud father and husband perhaps chief among them.

We made our way down to the patient’s room, where Dr. Cly’s first case of the day was waiting with family. I stood in the corner, notebook tucked under my arm so as not to announce my presence too loudly. Since scheduling the procedure, the patient had reevaluated her original plan (and received some push back from her well-meaning grandmother) and wanted to change things just a bit, a theme that I discovered runs rampant in the realm of reproductive health. Unphased, Dr. Cly walked her through the pros and cons of all of her options, eventually helping her land confidently on a care plan that involved a reversible technique; something to suit both her and her grandmother’s wishes.

I turned to leave but caught Dr. Cly’s voice and stopped on my toes. “Now if we can all join hands and say a quick prayer over this young woman,” he suggested. I reached for her mother’s hand on my right, Dr. Cly’s on my left, and gently closed my eyes. We stood in a circle and asked that the Lord protect her and all of us on this beautiful Monday morning.

In the women’s locker room, I changed into scrubs quickly. As Dr. Cly and I walked to the operating room, I asked if he preferred days in the OR over the delivery room.

“No way! I mean I love it, but the deliveries are what drew me to this whole thing to begin with,” he said. “I was actually going to school to be a lawyer. I was pre-law at the University of Dayton and we had to take a biology class. They showed us the ‘Miracle of Life’ video, which, I don’t know if you’ve seen it, but it documents a baby, from conception to birth. As soon as I saw the part with the actual delivery, I said ‘That is amazing! That’s what I am going to do.’ I left the class and called my mom to tell her I was going to be a doctor and deliver babies. That was it. I changed my major the next day.” A sentimental smile spread across his face, disappearing only as he drew his mask over his mouth.

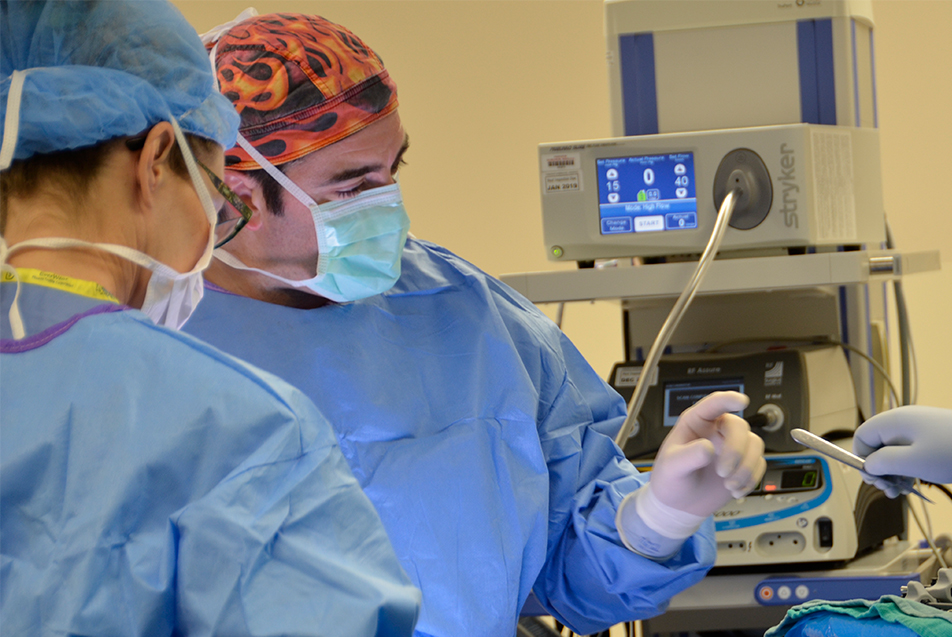

The staff took a timeout to review the morning’s case, then went about the fluid waltz of performing surgery. I looked up at a screen over my shoulder, deep red and soft pink shapes coming in and out of the frame.

“This is her uterus,” Dr. Cly offered, sensing my complete lack of recognition in regards to the anatomy in focus. “These white areas are ovaries,” he went on. Every so often he would stop and take a photo of the procedure. “I find that it helps them understand and answers a lot of questions,” he said. “Plus, then they can see that everything looks OK from an overall health perspective. There isn’t any cancer, for example.”

My eyes stayed fixed on the screen as he narrated this tour through the pelvic cavity. As a non-clinical Parkview team member, it always astounds me how different our organs look close up, as opposed to the diagrams we ponder on checkup room walls and in textbooks. In reality, the structures are flowing, pushing, breathing to facilitate function. These rare moments in the OR offer a glimpse at the life-giving glory of our bodies and I’m thankful, always, for the reminder.

As the patient requested, Dr. Cly performed the laparoscopic surgery, working slowly and thoroughly, collecting her reproductive history. “This is from her C-section,” he said. “This is from a hernia repair.” He didn’t need a file to familiarize himself with his patient. He let the scars and tissue tell her story.

This procedure fell outside of Dr. Cly’s typical surgery schedule, which occupies his working hours most Thursdays and Fridays. On these days, aside from some time designated for his Centering Pregnancy group prenatal visits, you will find the physician sitting at a da Vinci robotic surgery machine.

“When I was doing my residency at the University of Dayton in the late 1990s, this company took a bunch of us to see a new laparoscopic machine. It was so futuristic and cool, and they let us play with it for a bit. Years later, I saw the da Vinci truck in the parking lot at Parkview and I heard that the Parkview Heart Institute purchased one for their surgeons to use. Fortunately for me, the original heart surgeons didn’t use it after the first couple cases, so I asked if I could use it as well. This started happening with surgeons and OB/GYNs all over the country, and eventually the University of Michigan started a conference so OB/GYN physicians could train on da Vinci.”

Dr. Cly was the first OB/GYN in this area to use the laparoscopic tool to treat several key conditions, including endometriosis, and performing hysterectomies. Although the procedures took him a bit longer with this method initially, the obvious benefits, which included a smaller incision, reduced pain and faster healing time, were enough to urge him on.

“My Eureka! moment came when I did a hysterectomy on a 350-pound patient using da Vinci. The next day, at 9 o’clock in the morning, she was up, dressed and ticked off that I hadn’t been by to release her. Normally, that patient would have required a 3-5-day hospital stay and a 6-week recovery.”

Dr. Cly has served as a mentor for many other physicians who have come to rely on da Vinci methods in the OR. He’s also expanded his own knowledge and offerings on the robotic tool.

“For a patient experiencing ovarian cysts, for example, we can pull the cyst away from the ovary and save it, instead of removing the ovary entirely. As long as part of it is still functioning it will continue to produce eggs and hormones.”

Dr. Cly eventually graduated to treating pelvic prolapse with da Vinci, making him one of only two surgeons in Parkview Physician’s Group who can do so. The operation takes 3-4 hours and often involves collaboration with a urologist trained on the machine as well.

After the morning’s procedure was complete, I changed back quickly, picking up on comments that Dr. Cly’s team back at the office was making every effort to help him stay on time. A second note I made early in the day was that Dr. Cly has a lot of women to answer to. His skilled staff aside, he had 29 patients scheduled to see him that Monday, all female, all a priority.

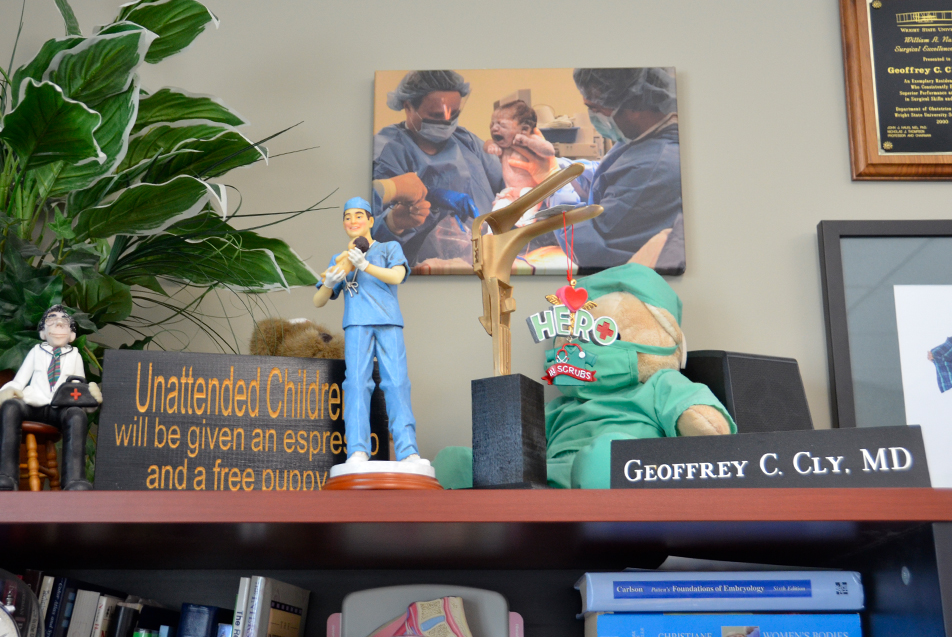

We tailed each other over to the parking garage at Carew Medical Park and took the elevator up to his offices on the third floor. The space was warm and welcoming. At Dr. Cly’s request, music plays throughout in an effort to help patients and staff feel at home and relaxed. While most physicians split their time between the Randallia campus and Parkview Regional Medical Center, Dr. Cly decided to stay exclusively in the Carew offices. “I had been moving around since the early 2000s and I just wanted to have one office. Plus, I was missing deliveries and that’s my favorite part.”

As he pulled up patient files on his computer, I took in the various tchotchkes on his shelves; gifts from family and patients. But it was a picture of Dr. Cly dressed as a goofy old time pilot in a blue Santa suit and Mr. Potato Head helmet hanging behind his desk that served as a clue to perhaps the biggest surprise of the day. As it turns out, in addition to a brief time in high school when he considered becoming a priest, and his stint as a pre-law major, it’s hard to imagine, but Dr. Cly was almost a professional mascot.

“I was third place in the nation for college mascots as Rudy Flyer my senior year. I went to mascot camp and did all sorts of crazy things, like swinging across the gymnasium on ropes. I thought about going pro, but I’d already been accepted to medical school. That’s one of my only regrets, just because I think it could have been so cool.”

And a far cry from the immense responsibilities of his current role, the logistics of which began unfolding rather rapidly after our arrival. There was a very defined sequence. Before each patient visit, Dr. Cly would consult his notes on his computer. He would brief me on the case, why we were seeing them today and then he would, say, “Ya ready, Gibbs?” and in we’d go. (Gibbs is Kaileina Gibbs, CMA, who worked with Dr. Cly throughout the day.) He would perform the exam, then we would return to his office so he could consult his notes for the next patient. In that time, he never looked ahead. He gave his full attention to the woman waiting in the room he was about to walk into. It was a tireless revolving door of diligence and direction.

Within an hour, I started to notice a trend. While speaking with a patient before her exam, Dr. Cly asked how she was feeling about her divorce. Then, a few patients later, he inquired about an unfortunate paternity situation.

“How did you remember that?” I asked. “What all do you put in your notes?”

“Oh gosh, anything that I believe could be affecting the patient,” he said.

That might be an abusive relationship, or a new grandchild or a vacation to Rome. If Dr. Cly finds it noteworthy, he adds it in and goes back to refresh his memory before each and every encounter. This is just one element of Dr. Cly’s personal approach that makes him exemplary in his field. It is a tactic that nourishes the delicate threads of trust necessary for a true doctor-patient connection.

“I treat people the way I would want to be treated,” he shared. “I want to take the time to get to know them. For some of these women, it’s just nice to have a man who will listen. This might be their only opportunity to ask questions about their health. If they need to talk about abuse or their sex life, I give them that chance.”

Maybe that approachable demeanor comes from his West Virginia roots, where he grew up with his mother as a self-proclaimed “mama’s boy” and perpetual good guy. Or maybe it’s a product of his own life experiences, which he reflects on and accesses to relate to patients regularly.

Along with the usual medical questions, Dr. Cly asks things like, “Do you feel peaceful inside?” and offers encouragement, like “God bless you, I’m proud of you for being strong and making the best decision for you and your family.”

If you have the time to listen, Dr. Cly has the repository of memorable cases that transformed his philosophy on medicine and shaped his approach to healing to share. One particular case – one that forever altered the scope of his work – involved a special patient he treated very early in his career.

“I cared for this young woman all through her pregnancy. And then, out of the blue, her baby was stillborn,” he recalled. “And I just couldn’t understand. Why would something like that just happen? Why, when a million things have to go right to create a life and then you make it all the way through the pregnancy, would it suddenly all just go away? I decided right then that I would dedicate myself to helping women who had experienced a miscarriage or recurrent miscarriages. It’s not that I’m inventing new treatments, I’m just trying different things and giving them hope. I actually still talk to that patient quite regularly.”

And it’s the trying and the hope-giving that suit him so well. Dr. Cly likes to solve problems. He admits, it’s exhausting, answering questions and trying to find solutions for eight straight hours. But he’s determined to make it look different, and feel different, and be different. “I had this high school girl come in, and she had an irregular pap smear. So, I asked her how many partners she’d had and it was a significant number, and I just thought, ‘Why is no one talking to this girl about the risks and why does she keep changing partners?’ So I talked to her. And what she really wanted was just to be loved. She couldn’t understand why all of the high school boys kept leaving her after they had sex. Later, she thanked me and told me I talked to her more about relationships and sex than her dad.” I saw this type of genuine concern replicated time and again in my hours with him. He asked about the big things – the breakups, the life changes – and the patients seemed grateful he cared enough to do so.

There are countless nuances to Dr. Cly’s craft because, among other intricacies, dealing with fertility is dealing with families. And dealing in the business of families means reckoning with love, distrust, complications, joy and miracles. Often not in that order. Never all at once. Add to that the force that is the maternal instinct. Dr. Cly’s patients aren’t just asking for medical intervention. Often times they are asking him to influence acts that are ultimately far out of any human’s hands. They want their babies to come on certain days, in certain circumstances. They want him to predict the future and guide them through it, which he does, to the best of his abilities.

All day, most days, Dr. Cly cares for women. Young women. Pregnant women. Older women. Scared women. Tired women. Frustrated women. Elated women. Heartbroken women. He encourages those who are approaching motherhood, and supports those who desire to move onto the next chapter. He comforts the patient, the spouse, the parent (often a mother herself) and he invests in each and every narrative.

He asks about scars, both the ones he can see and the ones he can sense. He spends the extra 15 minutes it takes to get the laugh or to get the truth, because in the end, both matter. His fascination with the miracle of life hasn’t been dulled or dimmed by years of cases. If anything, his commitment seems more resolute.

The writer Brene Brown said, “When we deny the story, it defines us. When we own the story, we can write a brave new ending. Owning your story is the bravest thing you’ll ever do.” Hours after I parted ways with Dr. Cly that evening, just a few cases left on his agenda, I curled up to go back through my notes. I had page after page filled with stories. Stories of overcoming the odds. Stories of devastating loss and the road to get back. Stories of unspeakable joy. Stories collected by a healer in the heroines’ most vulnerable hours. It would seem that in the midst of exams and deliveries and hours in the OR, Dr. Cly manages to pull off one of the biggest miracles of all: He helps women find their bravery. He helps them own their stories, simply by caring enough to ask about them.

“Life’s not easy, but there is a purpose to it,” he said. “Find your purpose or complete your journey and the whole thing becomes a lot richer. I feel like I’m on the journey.”